Nibbles Part 2

by Hez

Web Fingerprinting

Focusing now on the web server running on port 80, the first suggestion from HTBA is to run whatweb to try and enumerate what web technologies are present on the web server.

$ whatweb 10.129.202.255

http://10.129.202.255 [200 OK] Apache[2.4.18], Country[RESERVED][ZZ], HTTPServer[Ubuntu Linux][Apache/2.4.18 (Ubuntu)], IP[10.129.202.255]

Nothing new there. So let’s finally check the site out in a browser.

Very helpful…

Checking the page source does show an interesting comment, though…

<!-- /nibbleblog/ directory. Nothing interesting here! -->

While funny, checking webpage sources, especially for comments left by developers, can be way more helpful than it should be.

HTBA also suggests pulling the page source locally with cURL: curl HTTP://<target_ip_address>, which is also helpful in case you lose access to the webpage sometime in the future.

Now that we do know a directory that’s probably interesting, it’s a good idea to re-run the recon steps we did before, so we’ll re-run whatweb on our newly discovered directory. It’s also important to know that whatweb doesn’t spider or try to find these hidden directories, so it only works with what you give it. Yet another reason to have a good grasp on what your tool is doing.

$ whatweb http://10.129.202.255/nibbleblog

http://10.129.202.255/nibbleblog [301 Moved Permanently] Apache[2.4.18], Country[RESERVED][ZZ], HTTPServer[Ubuntu Linux][Apache/2.4.18 (Ubuntu)], IP[10.129.202.255], RedirectLocation[http://10.129.202.255/nibbleblog/], Title[301 Moved Permanently]

http://10.129.202.255/nibbleblog/ [200 OK] Apache[2.4.18], Cookies[PHPSESSID], Country[RESERVED][ZZ], HTML5, HTTPServer[Ubuntu Linux][Apache/2.4.18 (Ubuntu)], IP[10.129.202.255], JQuery, MetaGenerator[Nibbleblog], PoweredBy[Nibbleblog], Script, Title[Nibbles - Yum yum]

This does give us some more detail. After following the 301 redirect, whatweb found that we get issued a PHPSESSID Cookie, implying the usage of PHP. We also see that HTML5 and JQuery are being used and an interesting blogging engine called Nibbleblog. A quick google search will pull up the homepage, and checking the project’s GitHub shows that it’s not being maintained anymore. Oof.

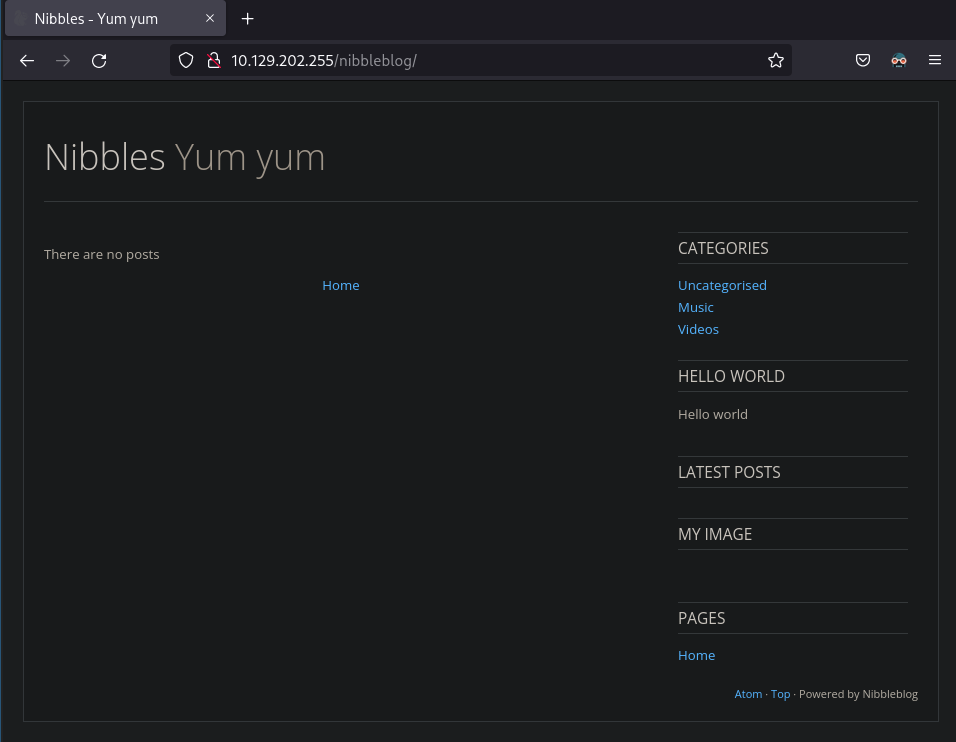

Let’s check the page out in a browser.

Pretty barren. Clicking the links doesn’t do anything, either.

Let’s see if there are any known exploits for Nibbleblog itself. We’ll google nibbleblog exploit and find this post on Rapid7’s Exploit Database, meaning there’s probably a Metasploit module for this. Excellent news, but before we rush to point Metasploit at our problem and expect it to do our work for us, we should read the exploit to ensure we know what it’s doing. Throwing random exploit code we can’t explain at our target is NEVER a good idea. I know it’s work, but you don’t have to spend years learning Ruby to at least get an idea of how a Metasploit module works.

Starting with the description, we see that this exploit is for “an authenticated remote attacker to execute arbitrary PHP code.” So we need to be authenticated first, which we haven’t done. Had we just shot Metasploit at this, we wouldn’t get anywhere. Once we do get authenticated, though, we should be easily able to upload PHP code and get a shell.

If our goal is to exploit a host, like it usually is with HTB, we should always consider the objective: getting a shell on a host. This differs from the focus of a more broad pentest or bug-bounty setting. Getting a shell is still significant in those cases, but exploiting other users and web-based vulnerabilities is also on the table.

The description also tells us this was tested on Nibbleblog version 4.0.3. At this point, I would probably want to go hunting for a version number on the webpage, but for this exercise’s sake, HTBA implies that we’ll be using this exploit later, so there’s a good chance it’s vulnerable. In other cases, it is crucial to ensure your exploit code works on a given service version.

Exploit description out of the way, deep breath, we’ll actually read the exploit source code. The link is on the Rapid7 page here. Having a good understanding of Ruby or at least Object-Oriented Programming principles, will really help here. You don’t need to be developer-level and have written 30 different Ruby projects. You just have to be able to read and have a grasp on the code, not be good enough to write it yourself.

Based on what we know about the exploit, we’ll probably be uploading a payload and probably doing that after we log in somewhere. So some questions we should be asking are:

- Where are we logging in

- How are we uploading the file

Answers for these, we can hopefully find in the exploit code.

We see some options towards the start.

register_options(

[

OptString.new('TARGETURI', [true, 'The base path to the web application', '/']),

OptString.new('USERNAME', [true, 'The username to authenticate with']),

OptString.new('PASSWORD', [true, 'The password to authenticate with'])

])

Indicating we’ll need to tell Metasploit our credentials, and Metasploit will log in to the application for us.

We also see the URI being used later here.

res = send_request_cgi(

'method' => 'GET',

'uri' => normalize_uri(target_uri.path, 'admin.php'),

'cookie' => cookie,

'vars_get' => {

'controller' => 'settings',

'action' => 'general'

}

)

Telling us that there should be an admin.php page somewhere. Probably where we’re going to be authenticating.

Skipping over a chunk of code that looks like it handles authenticating and preparing our payload, we see this.

vprint_status("Uploading payload...")

res = send_request_cgi(

'method' => 'POST',

'uri' => normalize_uri(target_uri, 'admin.php'),

'vars_get' => {

'controller' => 'plugins',

'action' => 'config',

'plugin' => 'my_image'

},

'ctype' => "multipart/form-data; boundary=#{data.bound}",

'data' => post_data,

'cookie' => cookie

)

This looks like we’re uploading the payload using a plugin for nibbleblog called my_image.

I highly encourage you to look at the source code yourself. This is the literal difference between skids and hackers here. It’s a spectrum, and the more you understand the underlying solution to the problem, the less skiddy you’ll be.

Think of it like every time you use a tool, script, or Metasploit module, you’re stacking on another layer of abstraction. You, as the actual tester, need to cut through as much abstraction as possible to be able to communicate or properly utilize your exploits. This is a topic for another time, but considering this would be the first engagement for someone who just started on HTB, these things are essential.

So we know admin.php is likely to be a critical page, but let’s see if there are any other helpful pages or directories.

Directory brute-forcing with Gobuster will find the common ones.

$ gobuster dir -u http://<target_ip_address>/nibbleblog/ --wordlist /usr/share/dirb/wordlists/common.txt Will run gobuster in directory/file enumeration mode on the -url for our target using the --wordlist common.txt from the dirb tool. This wordlist should exist on all Kali installs, but if you don’t have it, installing dirb should populate it.

You’ve got plenty of options for Wordlists. If you have access to the internet on your engagement, Daniel Messler’s SecLists is very well recommended and maintained at the time of writing. (He also has a fantastic newsletter if you’re into that kind of thing)

$ gobuster dir -u http://10.129.203.82/nibbleblog/ --wordlist /usr/share/dirb/wordlists/common.txt

===============================================================

Gobuster v3.1.0

by OJ Reeves (@TheColonial) & Christian Mehlmauer (@firefart)

===============================================================

[+] Url: http://10.129.203.82/nibbleblog/

[+] Method: GET

[+] Threads: 10

[+] Wordlist: /usr/share/dirb/wordlists/common.txt

[+] Negative Status codes: 404

[+] User Agent: gobuster/3.1.0

[+] Timeout: 10s

===============================================================

2022/09/11 03:22:22 Starting gobuster in directory enumeration mode

===============================================================

/.hta (Status: 403) [Size: 303]

/.htaccess (Status: 403) [Size: 308]

/.htpasswd (Status: 403) [Size: 308]

/admin (Status: 301) [Size: 325] [--> http://10.129.203.82/nibbleblog/admin/]

/admin.php (Status: 200) [Size: 1401]

/content (Status: 301) [Size: 327] [--> http://10.129.203.82/nibbleblog/content/]

/index.php (Status: 200) [Size: 2987]

/languages (Status: 301) [Size: 329] [--> http://10.129.203.82/nibbleblog/languages/]

/plugins (Status: 301) [Size: 327] [--> http://10.129.203.82/nibbleblog/plugins/]

/README (Status: 200) [Size: 4628]

/themes (Status: 301) [Size: 326] [--> http://10.129.203.82/nibbleblog/themes/]

===============================================================

2022/09/11 03:23:09 Finished

===============================================================

Going down the list:

- .hta - 403 Forbidden

- .htaccess - 403 Forbidden

- .htpasswd - 403 Forbidden

These are dotfiles to configure the Apache web server.

- /admin - redirects to admin.php

- /admin.php - our admin page to log-in to

- /content - open directory

- /index.php - Nibbleblog home page

- /languages - open directory

- /plugins - open directory (There’s the my_image plugin we need)

- /README - setup for Nibbleblog (confirms version v4.0.3)

- /themes - open directory

Now our main hurdle is logging in. We’ve confirmed that our exploit will work if we can authenticate, but we must get in first. Trying some default user:pass combinations is a good start. Trying these is always a good idea because people are lazy and it doesn’t take much time to do. In this case admin:admin and admin:password doesn’t yield anything. Eventually, we’d get locked out by the web app, so brute-forcing is off the table, as is often the case.

Next, we should google Nibbleblog to see if they have any default credentials, but we’ll find that the credentials are set at install. After that, we should try using some of the common keywords in the application and try them as credentials.

HTBA touches on this in the material, but making wordlists out of keywords on our target is often very helpful. In real life, this would entail including company and product names in our brute-force wordlists.

So as we poke around the directories we found earlier, we can find a users.xml that confirms a user with the username admin, which does half of our work for us and makes guessing easier.

HTBA does mention using a tool such as CeWL to generate a wordlist from the keywords in a web app, but before we go that far, we should try a few more common ones, such as the box name. We also see the word nibbles in /nibbleblog/content/private/config.xml . as part of a recovery email.

Trying this, we find the correct credentials admin:nibbles.

The core lesson of these first two HTBA modules is that Recon/Enumeration is a repeatable and recursive process. Once we find a new host/server/directory/file/etc. we can then restart our recon process on each of those newly discovered assets until we’ve enumerated as much as possible about a target. This also means that after successfully exploiting the target, we will want to do recon again.

That’s for later, though; for now, we can finally get on to exploitation.

tags: walkthrough - nibbles - HTB